It’s Raining Cats! Hallelujah.

In the 1950s, the Dayak people of Borneo had a malaria problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) had the solution: eliminate the mosquitoes.

The plan worked - at first. Malaria cases went through the floor. Then the problems began.

The DDT used to eradicate the mosquitoes also killed a species of wasp that preyed on caterpillars. Caterpillars have a real taste for thatched roofs. So when the caterpillar population exploded, people’s roofs started collapsing.

The geckos that absorbed the DDT from the environment then became fatal to their natural predators, the cats. With the cats out of the picture, the rats multiplied and swarmed the villages, causing an outbreak of bubonic plague.

The Royal Air Force was reduced to the bizarre expedient of having to parachute in an army of cats from Singapore. So, what went wrong exactly?

Complex problems need multi-dimensional solutions

A jet engine is complicated. You can identify a broken or faulty part, replace it, and you’ve fixed the plane. You just need to be wicked smart.

Ecological systems are not complicated, but complex. That is, small, injudicious changes can have large, unpredictable, and often catastrophic results.

Rather than fixing one aspect alone, you need to address multiple dimensions simultaneously.

In the case of Borneo, this might have involved a combination of smaller biological interventions (e.g. targeting mosquito larvae), environmental management (clearing away standing water and improving drainage), and simple preventative measures such as insecticide-treated bed nets.

All of which are more practical and effective than commissioning an airborne regiment of felines.

The Longevity Conundrum

Longer life spans are often viewed as an impending social crisis.

This is a mistaken view in my opinion, primarily because it fails to account for the benefits of an older population, framing its members as pure recipients (e.g. social security) rather than potential contributors (e.g. entrepreneurs and caregivers).

The fixes proposed (raising the retirement age, saving more money) are like DDT. Meanwhile, deteriorating health and the plague of purposelessness run rampant, paving the way for a more drastic, desperate solution further down the path.

There are risks of living longer without planning for it. So the solution is to plan.

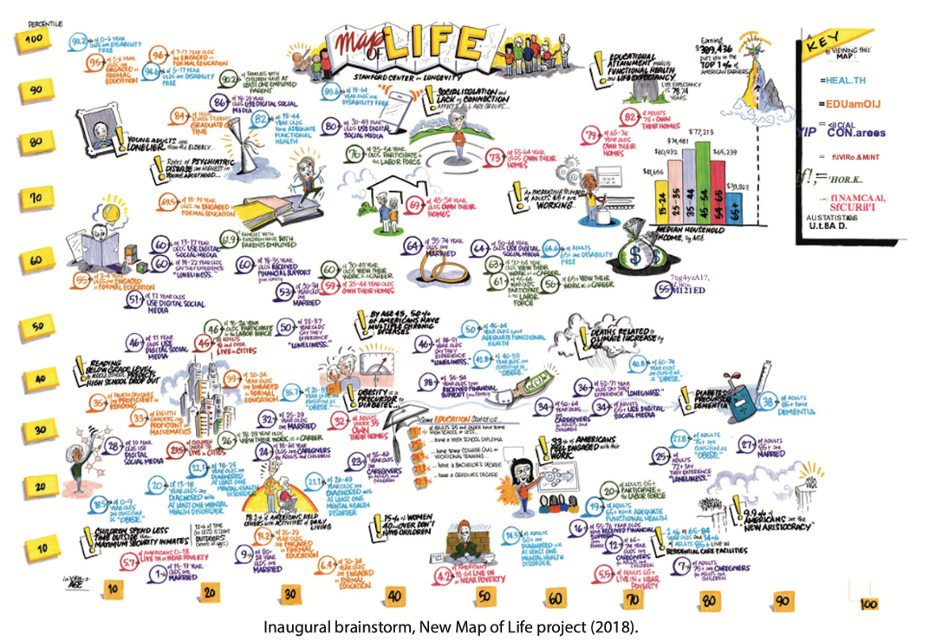

Stanford University’s ‘New Map of Life’ project was started to address this, drawing on 50 experts from different fields to craft multi-disciplinary solutions, covering the workspace, urban infrastructure, public health, and more.

As a financial advisor, I see this problem playing out at the level of the individual rather than the public policy level.

Just in case the federal government doesn’t move with the efficiency and lightning speed for which large bureaucracies are known and revered, I believe it’s wise for us to take matters into our own hands. And I also think we can.

Solving the problem of how to optimize, rather than maximize, the gift of life is a tall order. It definitely involves Money, but also Learning, Health, and many other domains (including Meaning).

Let’s explore these domains in more detail in future posts.